National Register of Historic Places

Lakewood Farm, Holland, Michigan

Prepared for the Historic Ottawa Beach Society and owners Patti and Ken Bing

March 2020 Submittal-Listing in progress With the exception of Lakewood Farm in Holland, Michigan, there has never been nor is there today in America a public attraction that is a combination working farm, horticultural garden, and zoo set on the shores of a major body and with an on-site owner’s mansion. This 4.23-acre property represents less than two percent of the 250 acres that was Lakewood Farm, owned and operated by George F. Getz from 1910 to 1933. However, this small piece of property is the largest lakefront parcel carved out of the farm and contains the most significant assemblage of the remaining buildings, structures, and objects of Lakewood Farm, and is therefore historically significant enough to represent the significant contributions of George Fulmer Getz to Holland and Park Township.

Lakewood Farm meets National Register Criterion B in the areas of agriculture, entertainment and recreation, and social history through its direct association with George Fulmer Getz, who through his development of Lakewood Farm into one of Michigan’s largest poultry producers, helped the local county fair through his participation became one of Michigan’s most successful fairs, supported the building of better roads in Holland, set aside a parcel of land for use as a public park, and developed a popular zoological attraction that led to the development of Holland, and surrounding areas, into a significant West Michigan tourist destination by drawing millions of people to Holland over the last seven years of its existence.

Lakewood Farm also meets National Register Criterion C because the architecture of three main extant buildings, and associated structures and objects, which were built and/or remodeled by Getz, are striking examples of modern architecture at the turn of the century as the Stick Style of the late nineteenth century transitioned to the new Arts and Crafts Movement taking place in the early twentieth century, and are in original condition as Getz built them or remodeled to the period in which Getz owned them.

Though not directly connected to Getz, Lakewood Farm illustrates a number of important political, social, and philosophical movements that coincided with Getz’s ownership and development of Lakewood Farm. Collectively, these various movements constituted the Progressive Era, a period in the first third of the twentieth century in which government and individuals responded with care, responsibility, and strength to the economic and social problems created by rapid industrialization in American.

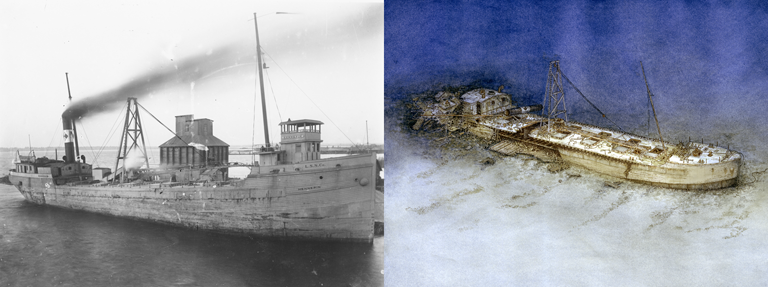

Shipwreck Hennepin, Lake Michigan, Van Buren County

Prepared for the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association

July 2007 Submittal-Listed 2008

First shipwreck listing in the Michigan waters of Lake Michigan

The Hennepin, originally a 208.8 foot long wooden hulled, steam powered freighter, was built in 1888. After a fire, the ship was rebuilt in 1902 and equipped with a self-unloading A-frame, boom and below-deck inclined hoppers. It operated as a self-unloading steamer and later, after its engine was removed, as tow-barge until it sank in Lake Michigan off South Haven, MI in 1927. Preserved upright and in intact in 230 feet of cold, clear, fresh water, It is considered eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places under criterion A, C and D because of its national (and international) significance: It is the world’s first self-unloading vessel, and it served as the paradigm for further developments in the self-unloading industry over the next century.

On Thursday, 8 May 1902, the steamer Hennepin left Buffalo with a cargo of Pennsylvania coal, bound for Milwaukee. Accompanying the Hennepin on that voyage would be Frank Merrill, general manager of the Lake Shore Stone Company of Milwaukee, which had just assumed ownership of the vessel a week earlier at the yard of the Buffalo Dry Dock Company. Merrill had what today appears to have been a visionary plan for the fourteen year-old wooden freighter, although it was a modest carrier compared to the four-hundred foot steel behemoths then being produced by Great Lakes shipyards for the iron ore trade. Within a month of her arrival at Milwaukee, the Hennepin would complete a metamorphosis into perhaps the most technologically significant vessel to sail the Great Lakes: In early June, the Hennepin emerged from the West Yard of the Milwaukee Dry Dock Company as the world’s first self-unloading bulk carrier, establishing the cargo-handling design paradigm upon which almost the entire Great Lakes bulk cargo fleet of over 2.7 million tons deadweight of shipping is today based, while influencing salt-water shipping practices as well, with, as of May 2007, self-unloaders making up over three million tons deadweight of the world’s ocean fleet sailing under the flags of twenty-four nations. Using the system of conveying belts, hoppered holds, and a deck-mounted unloading boom envisioned by Merrill and unknown engineers from Chicago’s Webster Manufacturing Company, virtually every one of these modern self-unloading vessels owes its pedigree to the Hennepin.

The genesis of this design paradigm is rooted in the very pragmatic project that Lake Shore Stone embarked upon soon after the turn of the last century, the creation of a state-of-the-art quarrying and stone distribution plant at the site of mammoth limestone deposits purchased by Lake Shore Stone’s syndicate of investors (including Great Lakes shipping entrepreneur E. G. Crosby) about thirty-three miles north of Milwaukee along the Lake Michigan shore. Certainly neither Merrill nor Webster Manufacturing consciously intended to devise a technologically revolutionary vessel, but rather the goal was to rationalize the transportation of stone, within the quarry site and plant for processing, but, especially, the efficient and cost-effective distribution of the quarry’s product to Lake Shore’s customers. The latter could be difficult since the quarry’s site near the lake would be over three miles from the nearest railroad connection, and the cost of extending a trunk line that distance would be prohibitively expensive. Undeterred by the seemingly unfavorable logistics, Lake Shore Stone decided to capitalize upon this drawback by eschewing rail service altogether and resolving to deliver its product solely by water. Out of this exigency, the conception of the Hennepin as self-unloader was born. Oddly, though, the significance of the Hennepin has been overlooked, the conversion receiving scant attention from the maritime and technical press when it first appeared, and whatever significance it did accrue being completely overshadowed and forgotten with the launching of the Great Lakes’ first new-build self-unloader, the Wyandotte, more than six years after the converted Hennepin entered service.

It has been one hundred-five years since the Hennepin loaded her first cargo at Stone Haven, Wisconsin, and unloaded it, in revolutionary fashion, at some unknown Lake Michigan port. Especially with the discovery in 2006 of the amazingly well-preserved wreck of the Hennepin in south-eastern Lake Michigan, it seems appropriate today to explore the history of this remarkable vessel, and in so doing restore her distinction as the technologically significant ship she was (and, as she remains today beneath Lake Michigan, still is).